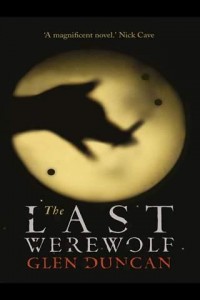

Sam reviews: The Last Werewolf

Nov.05, 2011, filed under books

![]() It was with a mix of sympathy and amusement that I read this article on iO9 responding to Glen Duncan’s piece on Colson Whitehead’s Zone One in the New York Times magazine. On the one hand we have the opening paragraph, which is clearly a rather unwarranted set of clichés and prejudicial presumptions:

It was with a mix of sympathy and amusement that I read this article on iO9 responding to Glen Duncan’s piece on Colson Whitehead’s Zone One in the New York Times magazine. On the one hand we have the opening paragraph, which is clearly a rather unwarranted set of clichés and prejudicial presumptions:

A literary novelist writing a genre novel is like an intellectual dating a porn star. It invites forgivable prurience: What is that relationship like? Granted the intellectual’s hit hanky-panky pay dirt, but what’s in it for the porn star? Conversation? Ideas? Deconstruction?

On the other we have the undeniable fact that Duncan clearly likes the work in question:

There will be grumbling from self-¬appointed aficionados of the undead (Sir, I think the author will find that zombies actually…) and we’ll have to listen for another season or two to critics batting around the notion that genre-slumming is a recent trend, but none of that will hurt “Zone One,†which is a cool, thoughtful and, for all its ludic violence, strangely tender novel, a celebration of modernity and a pre-emptive wake for its demise. If this is the intellectual and the porn star, they look pretty good together. For my money, they have a long and happy life ahead of them.

As it happens, Duncan’s The Last Werewolf has just moved off the top of my currently reading pile, and while I do have issues with Duncan’s blunt stereotyping of both intellectuals and porn stars, I think the only work he’s hurting is his own.

There is little chance of anyone trying to argue that The Last Werewolf is not a piece of genre fiction — and, before anyone starts screaming blue bloody murder, I do not think that this is a bad thing. Personally I get fed up with the insistence on labelling and hierarchies just as I get fed up with people who complain that action movies are somehow inferior simply because they tick all the boxes in the correct order. A book isn’t necessarily bad if it has as its primary goal the attempt to entertain. Not every single piece of written word has to have as its underlying purpose the statement of something profound about the human condition.

Nor is this to say that genre fiction can’t have something profound to say about the human condition. Genre fiction has a great deal to say about the human condition, and can be as thought-provoking as any so-called literary work.

Indeed, The Last Werewolf reads not so much as a depiction of lycanthropic existence as an attempt to pen a study of graceless ennui caused by over-stimulation, perhaps as an allegory for the internet generation’s desensitised state of been there, done that, got the two-girls-one-cup-happy-slap-t-shirt.

It did not light any fires chez Raven. It was a decent book — I have no showstopper complaints about it. I read it right through to the end and didn’t have to stop to rant (much) at any point. The prose was well-constructed, the imagery suitably lyrical, and the writing style avoided being clunky at any point. Marlowe’s character had a very definite voice, which meant the first-person perspective worked well. The idea that werewolves in this world were not eating the flesh of their victims so much as their histories and memories was a great one: taking a life meant taking a life, leaving one to infer that a werewolf’s lifespan was limited by sheer capacity more than biology. I enjoyed the throwaway trivia, for example that the expected pack structure was not there because female werewolves were in such short supply any other male would be regarded as a sexual rival. While I don’t want to give any plot spoilers, I appreciated that the female characters were, in their own way, powerful, and in some cases more powerful than gender stereotyping might lead one to expect.

Yet there were too many clichés spoiling the originality. Surely we have had enough of the vampire hates werewolf, werewolf hates vampire trope? Duncan went to some lengths to explain it but I sighed when Pratchett did it and Duncan does not have a pre-loaded soft spot in my heart as Sir Terry does.

I had issues with the pacing. The first two thirds of the book read like one of those movies in which there is lots going on but, inexplicably, nothing actually seems to be happening. This was no doubt meant to reflect Marlowe’s loss of enthusiasm for life, however it left me feeling oddly unmoved by any of the dramatic scenes, which meant that they were rendered not all that dramatic. Not enough was made of Marlowe’s access to the memories of those he had consumed and there were moments when I was left thinking “show, don’t tell”. At one point, in the last third of the book, there was an example of this so egregious I found myself thinking “FFS, couldn’t you at least try?”

Once again we had the assumption that living a long time means being able to accumulate vast riches. I suppose we wouldn’t have had all the globe-trotting if he’d been a pauper rather than someone for whom a cool twenty million is mere pocket change and I suppose one could argue that 200 odd years is enough time to get rich. Marlowe started off rich, though, which was irritating. I feel that there should be only so much disconnect between the reader and the protagonist, and there are big enough hurdles in getting to grips with the idea of being obliged to consume a person and his entire living memory once a month, as well as the idea of being so full of other lives and bored with one’s own life (not unhappy with it, but bored) that a violent death seems the preferable option without having to imagine being financially carefree in a way that only a tiny fraction of a percent of the world’s population experience.

You see, there was something that came close to being a deal breaker: Marlowe as a werewolf was the hybrid, bipedal, intelligent man-wolf type, nine feet tall and apparently unconstrained by conservation of mass.

I read advice somewhere to the effect that the reader will suspend disbelief for one thing and one thing only, so the writer would do well to make sure that one thing is the most implausible part of his story and that his plot hinges on it. Unfortunately for my enjoyment of this book the most implausible part of the story was that an ordinary-sized man can turn into a bipedal wolf-creature that is nine feet tall and stronger than Marius Pudzianowski. I let that slide, but then found myself unable to stop grousing about other major implausibilities.

Duncan’s review of Zone One left me wondering whether he thought it was the porn star or the intellectual who was aiming below his or her station in life. It is easy to infer he was describing a form of superiority when he wrote:

“…he’s a literary writer, hard-wired or self-schooled to avoid the clichéd, the formulaic, the rote.

Given that Duncan’s own work is a literary kind of genre fiction, taking this analogy at face value leads inevitably to one question: Does Duncan see himself as the porn star or the intellectual?

Because, quite frankly, in The Last Werewolf he has produced something that, while being entertaining and by no means the worst werewolf book I’ve ever read, fails either to deliver on the porn-star’s delight in his material or the intellectual’s hard-wired avoidance of rote and cliché.

If you want a good book about werewolves that examines the human condition, I recommend Kit Whitfield’s Bareback.