Sam reviews: Tricks of the Mind

Nov.13, 2011, filed under books, Reviews

![]() I’ve just finished reading, by way of light evening entertainment, Derren Brown’s Tricks of the Mind. Before I review it, I’d better ‘fess up about my ambivalent feelings towards Mr Brown.

I’ve just finished reading, by way of light evening entertainment, Derren Brown’s Tricks of the Mind. Before I review it, I’d better ‘fess up about my ambivalent feelings towards Mr Brown.

I am not fond of hypnosis used for the purposes of entertainment. This is an understatement so vast you could use it as an air-craft carrier and rescue the entire fleet of Harrier jump jets without them ever having to make a VTOL again. It takes an effort of persuasion or morbid curiosity regarding a particular stunt for me to watch any such performance on the television. The only Derren Brown show I have ever enjoyed was the one in which he went around debunking charlatans who were profiting from the gullibility of others (the school teaching blind people to see energy, in an effort to give them the kind of preternatural sight afforded by melange overdose to Paul Atreides, was an excellent case in point). I found his Zombie show repellent, believing, as I do, very strongly in the notion of informed consent.

My problem with Mr Brown comes down to that one critical idea: informed consent. As his show is one of magic and illusion, by its very nature he cannot explain how he does it. He is not the masked magician giving away Magic’s Greatest Secrets (not that I’m convinced by that, either). It is necessary for him to refrain from explaining himself and I appreciate that. It means, however, that the people he involves in his illusions and “experiments” cannot know precisely what he is going to do to them. It wouldn’t be so entertaining for the audience, otherwise. He needs them to be, as he describes the subject of Zombie in his book, of “naïve status”. Notwithstanding his insistence that

“It is very important to me that they enjoy themselves immensely and finish with a very positive experience of the process.”

I take issue with putting someone through any form of experience that, let’s be blunt, messes with his head, without prior full disclosure.

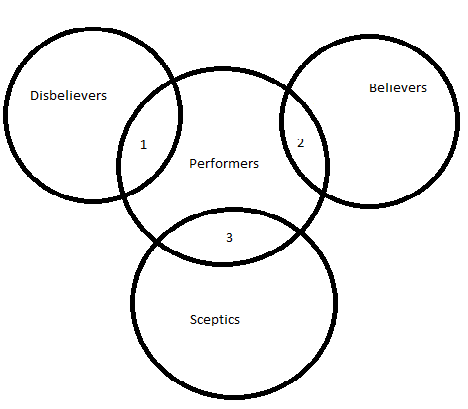

Mr Brown and I do share common ground, however. In a Venn Diagram of believers (e.g. Dion Fortune, say, or Kevin Carlyon), disbelievers (Richard Dawkins) and sceptics (Charles Fort), there is a cozy overlap of a set that includes everyone from Paul Daniels to Derek Acorah and Rupert Sheldrake.

There is an unfortunately large subset of performers that is contiguous with the middle set — the confidence tricksters, who know damn well they themselves are not psychic (whatever they feel about the supernatural in general) but who pretend to be psychic in order to extract money from gullible people. There is a special level of Hell reserved for people like them, and I expect the demon in charge is by now fed up with all the correspondence from me suggesting suitable punishments.

Snotgobbet, demonic secretary: You have email, my Lord.

Beelzebub, Master of Hell: FFS. It’s that mad Scottish woman again. How many is that this week?

Snotgobbet: That’s the third, my Monstrousness.

Beelzebub: She must be busy. Or slacking. We usually get more than that. Hmm. Do we even own that much chilli oil?

Snotgobbet: I will ask the Quartermistress, oh Ruler of Negative Empathy. If not, I am sure she can procure some from a suitable wholesaler.

Beelzebub: Oh, very well then. I’ll sign the order. Let me know when it comes in and fetch me the Dremmel.

Mr Brown and I share that particular distaste, at least.

The book promises to take you on “a journey into the structure and psychology of magic”. But we all know that what is written on the back of the book may not necessarily reflect what the author thinks the book is about. Mr Brown does this in the preface, explaining, by way of what is presented as an amuse bouche of an anecdote, that it teaches more about the various skills he employs to “entertain and sexually arouse the viewing few”.

The book promises to take you on “a journey into the structure and psychology of magic”. But we all know that what is written on the back of the book may not necessarily reflect what the author thinks the book is about. Mr Brown does this in the preface, explaining, by way of what is presented as an amuse bouche of an anecdote, that it teaches more about the various skills he employs to “entertain and sexually arouse the viewing few”.

On this front I have no disagreement. Mr Brown does indeed discuss the techniques he employs in his performances. He discusses mnemonics and hypnotism, sleight-of-hand and illusion, the power of persuasion, cold-reading, statistics, the way people are swayed by emotion, and the commonalities of the human experience that can be relied upon to make an individual treat a generic, stock answer as being a treatise on the dark corners of her soul. What it does not do is tell you exactly how he performs any one of his particular tricks. Indeed, he specifically says that he deliberately obfuscates so that what might look like a memory trick is actually manipulation and misdirection and vice versa.

Do not buy this book expecting to find out precisely how he pulled off Russian Roulette, or how he made a table levitate for Dr Robert Smith of UCL (although there is a good picture of the latter in the glossy middle pages). Do buy this book —or borrow it from a library— if you would like to read about Brown’s fascination with mnemonics and what he got up to as a student. Get it for the discussions of how what seems self-evident doesn’t hold up when analysed mathematically (always change your mind when presented with the last two boxes in the Monty Hall problem). If you liked the depiction of Hannibal Lecter’s Memory Palace you may well enjoy the exercises that start you on the road to creating your own.

He has a bee in his bonnet about pseudo-science, which is fair enough. He is only slightly less harsh about homeopaths and alternative medicine practitioners than Ben Goldacre, although makes no mention of TAPL. He does, however, lump a big section of the environmental lobby (including, by textual proximity, Greenpeace) in with the anti-MMR brigade, and misrepresents the Precautionary Principle used in environmental protection to a degree that makes it seem like environmentalists are as risk-averse as the mythical PC Health & Safety brigade (the one that insists that a banana must be straight just in case someone wishes to use it for a purpose other than consumption and runs the risk of injury as a result of excessive curvature).

He discusses, for instance, the banning of DDT and Carson’s Silent Spring, stating that he read in a book by Dick Taverne that “no tests have ever been replicated to show that DDT damages the health of human beings”, thereby missing the point, a bit, about Carson’s work. DDT’s effect (or lack thereof) on humans is only a small part of the picture. It was banned because of its effect on wildlife. Equally, GMO crops and the questions about growing them don’t have as much to do with their effect on the people eventually eating them as on the ecosystem as a whole. In trying to slam the green lobby for preferring “ideology over evidence” he shows a very human-centric view, and makes himself seem something of an idealogue —just a different sort of idealogue. One that sees the odd scientific fact and juicy rational tidbit and pounces on it, much as he describes those who believe in spiritualism and horoscopes as doing. I suppose that this only goes to show that we all do it, whether we like it or not, and a little amount of knowledge can be a dangerous thing.

I wouldn’t presume to offer an educated view on magic, memory and illusion. I appreciate Mr Brown’s desire to debunk charlatans and pseudo-scientists, but I do think he should be a bit more circumspect in how he chooses his examples.

That aside, the book is far more entertaining than his television shows. I still will not be persuaded that the more extreme examples of what he does are not a form of assault that is television-friendly.

At the end of the day, the book is also a performance. I doubt, despite his assurances, that the reader will learn much of the real Derren Brown. He swings from being deliberately self-deprecating to being self-aggrandising in a way that we are no doubt supposed to take tongue in cheek. On the other hand, as he says, who you are in an objective sense isn’t so much who you believe you are as how you present yourself. It’s not about what you think, feel or intend but about what you do. If what Derren Brown does is hypnotise people without asking into believing they are fighting zombies, or take potshots at the environmental movement because people who worry about the effect of bioaccumulative pesticides on apex predators are “eco-fundamentalists”, then I am content to carry on avoiding his shows and let him make his money from people who enjoy that sort of thing.

But I might be persuaded to read another of his books.

November 13th, 2011 on 15:09

I’ve had this book on my wish list on Amazon for ages but have never quite been in the right move to put it in my basket. I’m still in two minds about whether I want it. I did get his recent book not long after arriving and enjoyed that but there’s something about him that has put me off getting this. There is a certain smugness about his writing and I think you put your finger on it when you say that he’s just as idealogical in his own way but doesn’t seem to recognise it in himself. It’s probably also because, as you also say, I knew that it was unlikely to give away much about him as a person – he is a master at presenting a front and I don’t think he’d ever be able to stop doing that when he’s writing for an audience.

I have a whole heap of books from a reading list he had up on the Channel 4 web site. It’s been by working my way through those that I can usually figure out the method behind what he’s doing, even if I couldn’t replicate it myself. I’m unsurprised that this book doesn’t get you any closer to understanding his tricks. Still, it would be lovely to think that all those people who swear that he’s a latent psychic and just doesn’t know it would finally shut up and realise that it’s ALL trickery, he’s just exceptionally good at it.