books

Sam Reviews: Hide Me Among The Graves

by ravenbait on May.24, 2013, under books, Reviews

Hide Me Among the Graves by Tim Powers

Hide Me Among the Graves by Tim Powers

My rating: 3 of 5 stars

With Powers’s books I’m used to reading stories that make me feel the author knows his protagonists far better than anyone else who has ever written about them. They are mythic, mythical and full of iconography and symbolism. I read Declare and felt that the Cold War had been completely misinterpreted by historians the world over. I knew it hadn’t been, but that wasn’t the point. I felt that it had. I’m used to coming to the end of his books with a view of the world set slightly askew from the one I had when I started.

Sadly, Hide Me Among the Graves didn’t do that for me. Perhaps because there were both too many and not enough similarities to the London of The Anubis Gates, or perhaps because Christina Rosetti (familiar to more in these days of Doctor Who from the lines of “Goblin Fruit” quoted in the episode Midnight) as a character didn’t come through as the passionate, emotional, fey woman who wrote:

Yet come to me in dreams, that I may live

My very life again though cold in death:

Come back to me in dreams, that I may give

Pulse for pulse, breath for breath:

Speak low, lean low,

As long ago, my love, how long ago!

There’s always a danger, when using historical figures, that their depiction the work of fiction is not quite true to the reader’s idea of that person. It’s possible to wave away any differences by pointing out that this is a fictional work, and the universe of the story is not our universe. However, for me Powers’s magic as a storyteller has always been to make me believe, for the period in which I am reading, that it is our universe; and for ever after wonder if there are elements of his universe in this one and I just haven’t noticed.

I didn’t come away from this one feeling our universe might be slightly more magical than for which I’d previously given it credit. There was something missing, some spark that should have melded everything into a cohesive whole. For me it was rather like one of those dishes on Masterchef in which each component is beautifully cooked but the dish doesn’t quite work.

This is an accomplished work, but I’m used to being astonished by Powers, my perspective forever slightly changed. This was a very good story, well-written and entertaining. There is nothing wrong with that. It’s simply testament to Powers’s skill as a writer that previous exposure to his work left me disappointed with this one.

Sam reviews: Tricks of the Mind

by ravenbait on Nov.13, 2011, under books, Reviews

![]() I’ve just finished reading, by way of light evening entertainment, Derren Brown’s Tricks of the Mind. Before I review it, I’d better ‘fess up about my ambivalent feelings towards Mr Brown.

I’ve just finished reading, by way of light evening entertainment, Derren Brown’s Tricks of the Mind. Before I review it, I’d better ‘fess up about my ambivalent feelings towards Mr Brown.

I am not fond of hypnosis used for the purposes of entertainment. This is an understatement so vast you could use it as an air-craft carrier and rescue the entire fleet of Harrier jump jets without them ever having to make a VTOL again. It takes an effort of persuasion or morbid curiosity regarding a particular stunt for me to watch any such performance on the television. The only Derren Brown show I have ever enjoyed was the one in which he went around debunking charlatans who were profiting from the gullibility of others (the school teaching blind people to see energy, in an effort to give them the kind of preternatural sight afforded by melange overdose to Paul Atreides, was an excellent case in point). I found his Zombie show repellent, believing, as I do, very strongly in the notion of informed consent.

My problem with Mr Brown comes down to that one critical idea: informed consent. As his show is one of magic and illusion, by its very nature he cannot explain how he does it. He is not the masked magician giving away Magic’s Greatest Secrets (not that I’m convinced by that, either). It is necessary for him to refrain from explaining himself and I appreciate that. It means, however, that the people he involves in his illusions and “experiments” cannot know precisely what he is going to do to them. It wouldn’t be so entertaining for the audience, otherwise. He needs them to be, as he describes the subject of Zombie in his book, of “naïve status”. Notwithstanding his insistence that

“It is very important to me that they enjoy themselves immensely and finish with a very positive experience of the process.”

I take issue with putting someone through any form of experience that, let’s be blunt, messes with his head, without prior full disclosure.

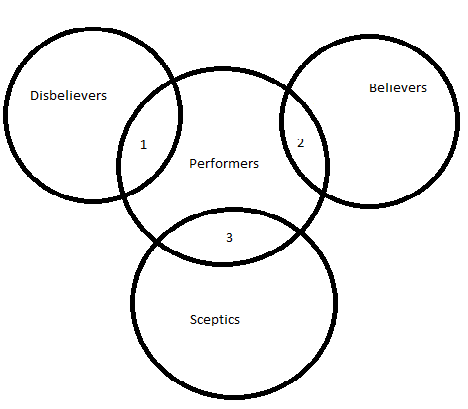

Mr Brown and I do share common ground, however. In a Venn Diagram of believers (e.g. Dion Fortune, say, or Kevin Carlyon), disbelievers (Richard Dawkins) and sceptics (Charles Fort), there is a cozy overlap of a set that includes everyone from Paul Daniels to Derek Acorah and Rupert Sheldrake.

There is an unfortunately large subset of performers that is contiguous with the middle set — the confidence tricksters, who know damn well they themselves are not psychic (whatever they feel about the supernatural in general) but who pretend to be psychic in order to extract money from gullible people. There is a special level of Hell reserved for people like them, and I expect the demon in charge is by now fed up with all the correspondence from me suggesting suitable punishments.

Snotgobbet, demonic secretary: You have email, my Lord.

Beelzebub, Master of Hell: FFS. It’s that mad Scottish woman again. How many is that this week?

Snotgobbet: That’s the third, my Monstrousness.

Beelzebub: She must be busy. Or slacking. We usually get more than that. Hmm. Do we even own that much chilli oil?

Snotgobbet: I will ask the Quartermistress, oh Ruler of Negative Empathy. If not, I am sure she can procure some from a suitable wholesaler.

Beelzebub: Oh, very well then. I’ll sign the order. Let me know when it comes in and fetch me the Dremmel.

Mr Brown and I share that particular distaste, at least.

The book promises to take you on “a journey into the structure and psychology of magic”. But we all know that what is written on the back of the book may not necessarily reflect what the author thinks the book is about. Mr Brown does this in the preface, explaining, by way of what is presented as an amuse bouche of an anecdote, that it teaches more about the various skills he employs to “entertain and sexually arouse the viewing few”.

The book promises to take you on “a journey into the structure and psychology of magic”. But we all know that what is written on the back of the book may not necessarily reflect what the author thinks the book is about. Mr Brown does this in the preface, explaining, by way of what is presented as an amuse bouche of an anecdote, that it teaches more about the various skills he employs to “entertain and sexually arouse the viewing few”.

On this front I have no disagreement. Mr Brown does indeed discuss the techniques he employs in his performances. He discusses mnemonics and hypnotism, sleight-of-hand and illusion, the power of persuasion, cold-reading, statistics, the way people are swayed by emotion, and the commonalities of the human experience that can be relied upon to make an individual treat a generic, stock answer as being a treatise on the dark corners of her soul. What it does not do is tell you exactly how he performs any one of his particular tricks. Indeed, he specifically says that he deliberately obfuscates so that what might look like a memory trick is actually manipulation and misdirection and vice versa.

Do not buy this book expecting to find out precisely how he pulled off Russian Roulette, or how he made a table levitate for Dr Robert Smith of UCL (although there is a good picture of the latter in the glossy middle pages). Do buy this book —or borrow it from a library— if you would like to read about Brown’s fascination with mnemonics and what he got up to as a student. Get it for the discussions of how what seems self-evident doesn’t hold up when analysed mathematically (always change your mind when presented with the last two boxes in the Monty Hall problem). If you liked the depiction of Hannibal Lecter’s Memory Palace you may well enjoy the exercises that start you on the road to creating your own.

He has a bee in his bonnet about pseudo-science, which is fair enough. He is only slightly less harsh about homeopaths and alternative medicine practitioners than Ben Goldacre, although makes no mention of TAPL. He does, however, lump a big section of the environmental lobby (including, by textual proximity, Greenpeace) in with the anti-MMR brigade, and misrepresents the Precautionary Principle used in environmental protection to a degree that makes it seem like environmentalists are as risk-averse as the mythical PC Health & Safety brigade (the one that insists that a banana must be straight just in case someone wishes to use it for a purpose other than consumption and runs the risk of injury as a result of excessive curvature).

He discusses, for instance, the banning of DDT and Carson’s Silent Spring, stating that he read in a book by Dick Taverne that “no tests have ever been replicated to show that DDT damages the health of human beings”, thereby missing the point, a bit, about Carson’s work. DDT’s effect (or lack thereof) on humans is only a small part of the picture. It was banned because of its effect on wildlife. Equally, GMO crops and the questions about growing them don’t have as much to do with their effect on the people eventually eating them as on the ecosystem as a whole. In trying to slam the green lobby for preferring “ideology over evidence” he shows a very human-centric view, and makes himself seem something of an idealogue —just a different sort of idealogue. One that sees the odd scientific fact and juicy rational tidbit and pounces on it, much as he describes those who believe in spiritualism and horoscopes as doing. I suppose that this only goes to show that we all do it, whether we like it or not, and a little amount of knowledge can be a dangerous thing.

I wouldn’t presume to offer an educated view on magic, memory and illusion. I appreciate Mr Brown’s desire to debunk charlatans and pseudo-scientists, but I do think he should be a bit more circumspect in how he chooses his examples.

That aside, the book is far more entertaining than his television shows. I still will not be persuaded that the more extreme examples of what he does are not a form of assault that is television-friendly.

At the end of the day, the book is also a performance. I doubt, despite his assurances, that the reader will learn much of the real Derren Brown. He swings from being deliberately self-deprecating to being self-aggrandising in a way that we are no doubt supposed to take tongue in cheek. On the other hand, as he says, who you are in an objective sense isn’t so much who you believe you are as how you present yourself. It’s not about what you think, feel or intend but about what you do. If what Derren Brown does is hypnotise people without asking into believing they are fighting zombies, or take potshots at the environmental movement because people who worry about the effect of bioaccumulative pesticides on apex predators are “eco-fundamentalists”, then I am content to carry on avoiding his shows and let him make his money from people who enjoy that sort of thing.

But I might be persuaded to read another of his books.

Sam reviews: The Last Werewolf

by ravenbait on Nov.05, 2011, under books

![]() It was with a mix of sympathy and amusement that I read this article on iO9 responding to Glen Duncan’s piece on Colson Whitehead’s Zone One in the New York Times magazine. On the one hand we have the opening paragraph, which is clearly a rather unwarranted set of clichés and prejudicial presumptions:

It was with a mix of sympathy and amusement that I read this article on iO9 responding to Glen Duncan’s piece on Colson Whitehead’s Zone One in the New York Times magazine. On the one hand we have the opening paragraph, which is clearly a rather unwarranted set of clichés and prejudicial presumptions:

A literary novelist writing a genre novel is like an intellectual dating a porn star. It invites forgivable prurience: What is that relationship like? Granted the intellectual’s hit hanky-panky pay dirt, but what’s in it for the porn star? Conversation? Ideas? Deconstruction?

On the other we have the undeniable fact that Duncan clearly likes the work in question:

There will be grumbling from self-¬appointed aficionados of the undead (Sir, I think the author will find that zombies actually…) and we’ll have to listen for another season or two to critics batting around the notion that genre-slumming is a recent trend, but none of that will hurt “Zone One,†which is a cool, thoughtful and, for all its ludic violence, strangely tender novel, a celebration of modernity and a pre-emptive wake for its demise. If this is the intellectual and the porn star, they look pretty good together. For my money, they have a long and happy life ahead of them.

As it happens, Duncan’s The Last Werewolf has just moved off the top of my currently reading pile, and while I do have issues with Duncan’s blunt stereotyping of both intellectuals and porn stars, I think the only work he’s hurting is his own.

There is little chance of anyone trying to argue that The Last Werewolf is not a piece of genre fiction — and, before anyone starts screaming blue bloody murder, I do not think that this is a bad thing. Personally I get fed up with the insistence on labelling and hierarchies just as I get fed up with people who complain that action movies are somehow inferior simply because they tick all the boxes in the correct order. A book isn’t necessarily bad if it has as its primary goal the attempt to entertain. Not every single piece of written word has to have as its underlying purpose the statement of something profound about the human condition.

Nor is this to say that genre fiction can’t have something profound to say about the human condition. Genre fiction has a great deal to say about the human condition, and can be as thought-provoking as any so-called literary work.

Indeed, The Last Werewolf reads not so much as a depiction of lycanthropic existence as an attempt to pen a study of graceless ennui caused by over-stimulation, perhaps as an allegory for the internet generation’s desensitised state of been there, done that, got the two-girls-one-cup-happy-slap-t-shirt.

It did not light any fires chez Raven. It was a decent book — I have no showstopper complaints about it. I read it right through to the end and didn’t have to stop to rant (much) at any point. The prose was well-constructed, the imagery suitably lyrical, and the writing style avoided being clunky at any point. Marlowe’s character had a very definite voice, which meant the first-person perspective worked well. The idea that werewolves in this world were not eating the flesh of their victims so much as their histories and memories was a great one: taking a life meant taking a life, leaving one to infer that a werewolf’s lifespan was limited by sheer capacity more than biology. I enjoyed the throwaway trivia, for example that the expected pack structure was not there because female werewolves were in such short supply any other male would be regarded as a sexual rival. While I don’t want to give any plot spoilers, I appreciated that the female characters were, in their own way, powerful, and in some cases more powerful than gender stereotyping might lead one to expect.

Yet there were too many clichés spoiling the originality. Surely we have had enough of the vampire hates werewolf, werewolf hates vampire trope? Duncan went to some lengths to explain it but I sighed when Pratchett did it and Duncan does not have a pre-loaded soft spot in my heart as Sir Terry does.

I had issues with the pacing. The first two thirds of the book read like one of those movies in which there is lots going on but, inexplicably, nothing actually seems to be happening. This was no doubt meant to reflect Marlowe’s loss of enthusiasm for life, however it left me feeling oddly unmoved by any of the dramatic scenes, which meant that they were rendered not all that dramatic. Not enough was made of Marlowe’s access to the memories of those he had consumed and there were moments when I was left thinking “show, don’t tell”. At one point, in the last third of the book, there was an example of this so egregious I found myself thinking “FFS, couldn’t you at least try?”

Once again we had the assumption that living a long time means being able to accumulate vast riches. I suppose we wouldn’t have had all the globe-trotting if he’d been a pauper rather than someone for whom a cool twenty million is mere pocket change and I suppose one could argue that 200 odd years is enough time to get rich. Marlowe started off rich, though, which was irritating. I feel that there should be only so much disconnect between the reader and the protagonist, and there are big enough hurdles in getting to grips with the idea of being obliged to consume a person and his entire living memory once a month, as well as the idea of being so full of other lives and bored with one’s own life (not unhappy with it, but bored) that a violent death seems the preferable option without having to imagine being financially carefree in a way that only a tiny fraction of a percent of the world’s population experience.

You see, there was something that came close to being a deal breaker: Marlowe as a werewolf was the hybrid, bipedal, intelligent man-wolf type, nine feet tall and apparently unconstrained by conservation of mass.

I read advice somewhere to the effect that the reader will suspend disbelief for one thing and one thing only, so the writer would do well to make sure that one thing is the most implausible part of his story and that his plot hinges on it. Unfortunately for my enjoyment of this book the most implausible part of the story was that an ordinary-sized man can turn into a bipedal wolf-creature that is nine feet tall and stronger than Marius Pudzianowski. I let that slide, but then found myself unable to stop grousing about other major implausibilities.

Duncan’s review of Zone One left me wondering whether he thought it was the porn star or the intellectual who was aiming below his or her station in life. It is easy to infer he was describing a form of superiority when he wrote:

“…he’s a literary writer, hard-wired or self-schooled to avoid the clichéd, the formulaic, the rote.

Given that Duncan’s own work is a literary kind of genre fiction, taking this analogy at face value leads inevitably to one question: Does Duncan see himself as the porn star or the intellectual?

Because, quite frankly, in The Last Werewolf he has produced something that, while being entertaining and by no means the worst werewolf book I’ve ever read, fails either to deliver on the porn-star’s delight in his material or the intellectual’s hard-wired avoidance of rote and cliché.

If you want a good book about werewolves that examines the human condition, I recommend Kit Whitfield’s Bareback.

Sam reviews…

by ravenbait on Feb.10, 2009, under books

![]() This is the view from our window today:

This is the view from our window today:

As much as I want to go out and play in the sunshine, or get some training in, I spent most of last night coughing and I’m still producing gallons of phlegm that bears a passing resemblance to fluorescein mixed with cornstarch.

Not only that but Frood is out until half ten tonight, and it’s not like I can go visiting (I can’t walk very far without feeling faint) or have anyone round (I’m contagious). So it’s just me and my nerms (those are ninja germs, for the uninitiated).

Bah.

It is my habit when trapped at home by nerms to read books. I don’t get much of a chance otherwise. My brain keeps finding other things to do. So far I’ve read James Herbert’s Once and I’ve re-read The Prestige.

James Herbert could be argued to occupy the same position in British horror literature (can I use that word?) as Stephen King does in American, at least in terms of popularity. The problem with Herbert is, to my mind, that he has always tended more towards slasher-fic than true horror. Oh, and the porn. Dear gods. The porn. I mean, I liked him when I was a teenager and still thought that Iron Maiden’s Eddie was just the coolest thing ever, but as I grew older I came to realise that a chainsaw-wielding maniac and some explicit passages about blow jobs do not a horrifying story make.

Once declared itself to be a fairy story, of sorts. I don’t know how it came to be on my shelf, but I knew I hadn’t read it, so I thought what the hell.

I swear that thing was ghost-written. Spelling mistakes. Grammar mistakes. Punctuation mistakes. Quotation marks missing in the strangest places. It fair put me off, I can tell you. But, all that aside, I’m sure that the explicit sex in Herbert’s earlier work wasn’t so, well, gratuitous. I don’t need 4 pages of our hero watching an undine masturbate. Really. Nor do I need almost an entire chapter describing how TEH EEEEBIL WITCH (called a Wicca in this, which I’m sure will delight all the Gardnerians in the audience) conducts lesbian drug rape on the physiotherapist. Including fisting.

No, no, and no. And, lest we forget, the entire plot resolves around the Messiah trope, played absolutely straight and by the numbers. Right down to being loved by the birds and bees, and dear gods, he’s a carpenter! If that weren’t enough, it’s explicitly stated that he is just like Jesus.

Better have a bucket handy.

The prose is shoddy, the story tedious, the pseudo-philosophical ramblings risible. To put it simply, this is one of those books that acts as discouragement to the aspiring writer, because you realise that the only way you’ll ever be a bestselling author is to produce absolute dreck.

And the same thing goes for Priest’s work. Prize winning, this was. Turned into a movie. With Hugh Jackman!

The grammatical structure is sound, and at least I don’t feel like it was written by Stewie from Family Guy with occasional help from Quagmire, as I did with Once. But still. I fail to understand what purpose the modern sections served, apart from to leave the reader with either a sequel hook or the possibility of the protagonist being still alive out there somewhere. None of the main characters provoked any sympathy. Their actions went beyond mere character flaws into a degree of obsession over something these days David Blaine does for free and for which trouble he has burgers thrown at him. The science was absurd, and the entire plot hinged on a MacGuffin that simply could not work. Can we all spell conservation of mass, boys and girls? Handwaving it away as all matter is energy and vice versa fails to take into account Einstein’s famous equation. I doubt Tesla, brilliant as he was, would have been quite so blasé about it.

I couldn’t enjoy it as a story of conflict between two obsessives, because Priest didn’t ever explore why their accounts of their lives varied so much. Besides, I didn’t care about them. I couldn’t enjoy it as a story about illusion versus genuine magic, because the magic was dressed up as pseudo-science and it annoyed me. I couldn’t enjoy it as a story about obsession and the lengths people will go to in order to cover up their secrets because the secondary characters in the story were given too little credit and too little depth. The efforts expended to keep the secrets and maintain the obsessions didn’t have the necessary concomitant feeling of the suffering of those who should be intimate.

And yet this is another bestseller and this one has won awards.

Today I’m going back to Bester and Zelazny. I’m ill. I need something good to read.